Uncertainty, Hope, And The Herring River Dike | #2 in the Herring River Restoration Series

How Mosquitos, Politics, and Science Continue to Define The Dike’s Future

By David B. Wright

Summer, and already Wellfleet is alive with mosquito talk. Pesticide control, second only to a Gaza cease-fire resolution, was again the most-discussed article at the recent Annual Town Meeting. More than 115 years and people are still anxiously asking: “How can I keep mosquitoes out of my yard?” Is this 2024 or 1909? While we don’t see men and horses veiled in mosquito netting as in “pre-dike” days, mosquitoes are once again a vexing nuisance. What impact will the Herring River restoration have? Did the building of the dike accomplish anything good? The two initial reasons for the dike were the eradication of mosquitoes and the creation of more arable land. Led by Capt. L.D. Baker, who built the Chequesset Inn, Wellfleet’s first hotel, the popular thinking was that the mosquitos would disappear once their marshland breeding grounds were drained. Out of affection and respect for the recently deceased Capt. Baker the Wellfleet Town Meeting approved the dike. Work began in 1908. So remote from town was the dike that participants in its ground-breaking ceremony arrived in The Cultivator, Capt. Baker’s cutting-edge gasoline-powered oyster smack.

Shortly thereafter the job supervisor arrived, and was housed in The Morning Glory, the beautiful Crocker House on Holbrook Ave., then owned by the Baker family. Twenty-five Italian laborers arrived at the river and built thatch-roofed huts carved out of the nearby hillside where they would remain right into the cold weather. A nearby hunting camp was rented, and a cook hired to cater to the crew. A pile-driving scow was constructed on the beach near the Wellfleet train depot. Bill Ryder, a contemporary eye witness, wrote, “The Italians would pull the empty carts to the top of the hill, load them up with sand, and let them roll down the hill to empty into the channel. For the western side of the dike, however, horses had to be attached to the carts for the hauling on tracks.” The dike itself was built around a wooden core, built with the help of the scow. Sand was used to fill in and around the wooden frame. The scow also hauled blocks of granite cut with hand-sharpened diamond drills which were hand-operated by the workers. Was everyone happy? No. Earle Rich, late local historian, was deeply saddened and outraged at what he saw as desecration of Mother Nature’s inexhaustible estuarial fish and shellfish breeding grounds. Clarice Daniels, reporting in The Cape Cod Standard Times, wrote about a Mr. Paine who had vowed that if the dike were built, he would never again enter town. “He lived into the 1930s, and never was known to come into town again. Horton’s store delivered his groceries, neighbors did his errands, he grew a beard and practically became a hermit,” she wrote.

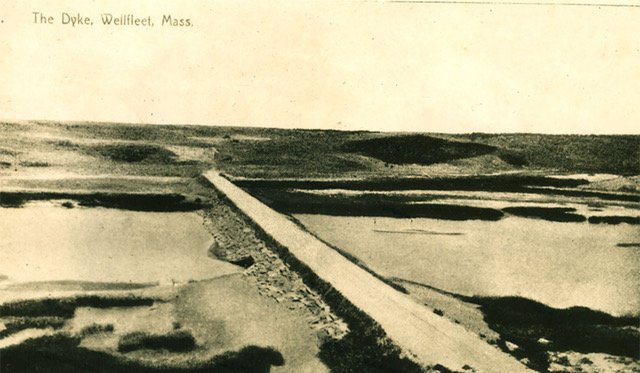

The newly-reconstructed Herring River dike as it appeared in 1975. Note that fifty year ago, the town’s hill were treeless as they were in 1908 when the first dike was built.

Most of the town remained in favor of the dike and its promise of a rich future in tourism. Perhaps nobody understood the dike’s potential challenges as well as benefits better than Dr. David Belding, the extraordinary marine biologist and M.D. who at the time was doing ground breaking research in Wellfleet that would serve as the foundation of modern aquaculture. "There are no real obstructions present to prevent the alewives from having free access to the excellent spawning grounds, provided the gate in the dike is tended regularly. What the fishery needs most is careful supervision, freedom from town politics, and a greater number of alewives permitted to reach the spawning grounds." Were his words heeded? The mosquitos never left, and ditching and spraying to control them continued through 1935, when the State assumed the responsibility for mosquito control, though still at the Town’s expense.

Modern environmentalists such as Richard LeBlonde bemoans the "loss of alewives and finfish and shellfish breeding and feeding habitats. Eel grass died, eliminating scallops, mussels and feeding grounds for black ducks and brants.” Dr. Derrick Alcott, in his four-year pre-doctoral study, found that half of the river herring that approach the dike never make it through the culverts. And this with the sluice gate fully open, unlike the original intention to open the culverts only when the herring were running.

Through the decades, the dike underwent many modifications and repairs. Likewise, the dike continued to raise political and social issues. By 1968, the sluice gate was rusted open, presenting an opportunity for a re-assessment of the whole scheme. Stacey May of the Conservation Commission argued a gradual return to pre-1909 conditions while Selectman Henry Atwood was asking, “Why do you want to wreck what it took 65 years to make?”

In 1908, Capt. Lorenzo Dow Baker’s pioneering gas-powered oyster boat was used to carry Wellfleetians to the then-remote Herring River to break ground on the town’s infamous dike.

The town voted in 1971 to virtually rebuild the dike. The work was completed in 1975. In 1977, the Dept. of Natural Resources ordered the town to open the sluice gate to 5.7 feet above mean low water level for the safe passage of alewives. Purportedly fearing law suits from the golf course and two house lots subject to flooding, the town refused to relinquish the hand-held crank that controlled water flow. It was quickly locked up in the Town Hall vault, though some local officials claimed…wink wink…to have no idea where it had got to when the state Attorney General’s office demanded it be relinquished.

What was originally a battle over environmental consequences suddenly emerged as matter of power and control over which government entity, local or state, would control the water flow. In 1983, John Portnoy, National Seashore biologist, with the support of the Association for the Preservation of Cape Cod, presented a plan – which later morphed into the river’s restoration project – for the gradual opening of the dike gates to restore the saltmarsh AND reduce the mosquitoes. In July, the Board of Selectmen, having undergone a generational shift, voted in agreement. The crank, 7 years after the State had demanded it, was mysteriously discovered and turned over to the State.

What will the restoration mean for the town? Will increasing water flow result in flooding similar to the Duck Harbor-related inundation experienced this winter? Will the mosquitoes be reduced? Will shellfishing be helped or hindered? No one can say with certainty. What is certain is that changes are planned to happen gradually. The restoration project’s spokespeople have been exemplary in their efforts to inform the public of their progress. But if you go to one of their outdoor talks, it might be smart to wear a mosquito veil.

David Wright is the curator of the Wellfleet Historical Society Museum and the author of The Famous Beds of Wellfleet: A Shellfishing History.